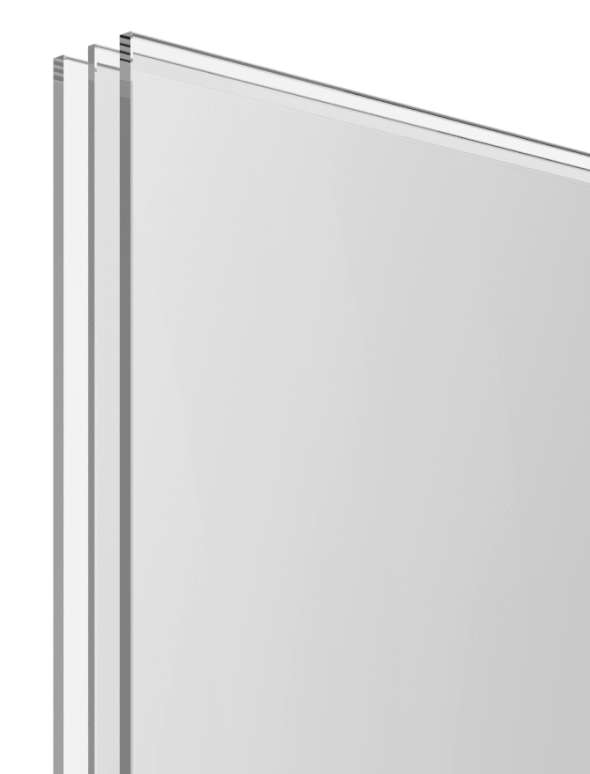

As the nights begin to get colder, condensation can appear on the surface of the glazing outside the home. This is known as external condensation and is normal for high-performance glazing, subject to local weather conditions. The picture is a classic example of external condensation, which is often mistaken for a failed unit (condensation within the sealed unit cavity).

Observing this picture shows condensation on one pane and not the other; this is also normal. One window has condensation, and the other doesn't due to the surface temperature and exposure of the affected pane of glass. It can be seen that the affected pane is at a different neglected pane. You can reasonably surmise that the affected pane is not as exposed to local weather conditions - wind and direct sunlight, meaning that the condensation has not evaporated as quickly as the unaffected window.

External condensation, while unsightly, is short-lived as the day progresses and temperatures rise. It is also a great visual indicator of how well the windows are performing. The insulation provided by the new windows prevents heat escape, and thus, the outer surface is cold, offering a surface for moisture to condense upon should weather conditions be apt. Older windows lose heat through them, thereby warming the external surface. This raises the temperature of the external pane and doesn't let the condensation settle.

Understanding that newer high-performance windows lose less heat and save money is crucial for homeowners, property managers, or individuals interested in understanding the behaviour of high-performance windows.